I've built NLP solutions for 15 years now. Thanks to ChatGPT and other large language models, everyone knows what NLP is, but here I'll write about what it was and what it was like before the LLM era. A "blast from the past" kind of piece, but hopefully you don't mind and find it interesting 😅

What Are NLP Problems?

Nowadays we mainly see generative AI: solutions that produce text/speech/images/videos, or perform small actions if it's an agent with access to tools. And of course you can interact with it by writing or speaking in ordinary language.

Before large language models that understand and can generate language with sufficient quality existed, we had to aim for smaller goals. The objective might be, for example:

- text classification (spam message, billing message, complaint, etc.),

- sentiment analysis (positive, negative, neutral),

- recommending similar texts ("read more about..."),

- finding entities (people, places, etc.) in text,

- text clustering, or

- predicting the future ('the next word is "you"').

Recommendations with an Ontology Engine

In 2010, I joined Leiki Oy, whose main product was recommendations. For example, on a news website, the solution would suggest more articles on the same topic or related topics next to the article being read.

Leiki Oy's recommendation engine worked based on ontology. An ontology is a collection of concepts and their relationships, which I'll try to describe by comparing it to Wikipedia: in Wikipedia, each concept has its own page (which the user reads), but there are also keywords and links to broader and narrower concepts. Thus, we can say that certain words relate to certain concepts, and that concept is close to or far from some other concept.

Leiki Oy's solution could analyze texts (what words and corresponding concepts they contain) and search for similar articles in the article database. Technically, we used regex (identifying article topics) and vector search (finding similar articles), as well as various search engine techniques like different indexing, normalization, and disambiguation algorithms. In addition to recommendations, we also worked on classification, sentiment analysis, and entity extraction problems.

Using ontology for text analysis was Leiki's specialty. Vector search technologies were already common knowledge, but transforming text into vector form in a way that makes the vector representation actually useful—there were no universally recognized and proven methods for that.

Early Machine Learning and Statistical Methods

At that time, NLP machine learning and statistical methods were quite modest. If ontology-based methods weren't used, the vocabulary might be converted to one-hot vectors or other text features might be used. For example, if a message has lots of exclamation marks, capital letters, and words like "MONEY" and "RICH", that's a reasonably good sign that it might be a SPAM message.

Word2Vec from 2013 was the first time I felt that linguistic phenomena were opening up to machine learning methods. In Word2Vec, word vectors are trained based on word co-occurrence, and these vectors have interesting properties, such as vector arithmetic operations producing semantically meaningful results. For example, with vectors for "king", "man", "queen", and "woman":

king - man + woman ≈ queen

Another similar word embedding algorithm was GloVe from 2014.

Word embedding methods worked well with machine learning methods (or are machine learning) and word embedding models and networks utilizing them were developed everywhere. Soon major players began publishing their word embedding models (models that convert text to vectors) for public use. For example, Facebook released fast FastText models trained on large datasets for different languages.

Solutions utilizing machine learning methods also started appearing in homes at the same time: smart TVs produced and understood speech. Soon voice-understanding home control systems like Alexa appeared.

Chatbots Before Large Language Models

Various messaging platforms like WhatsApp and Messenger have been hugely popular for a long time. In 2016, I worked at a company called Jongla. Jongla was a messaging platform whose business angle was a lightweight messaging client, targeting especially developing economies. I got to build bots and bot algorithms for Jongla.

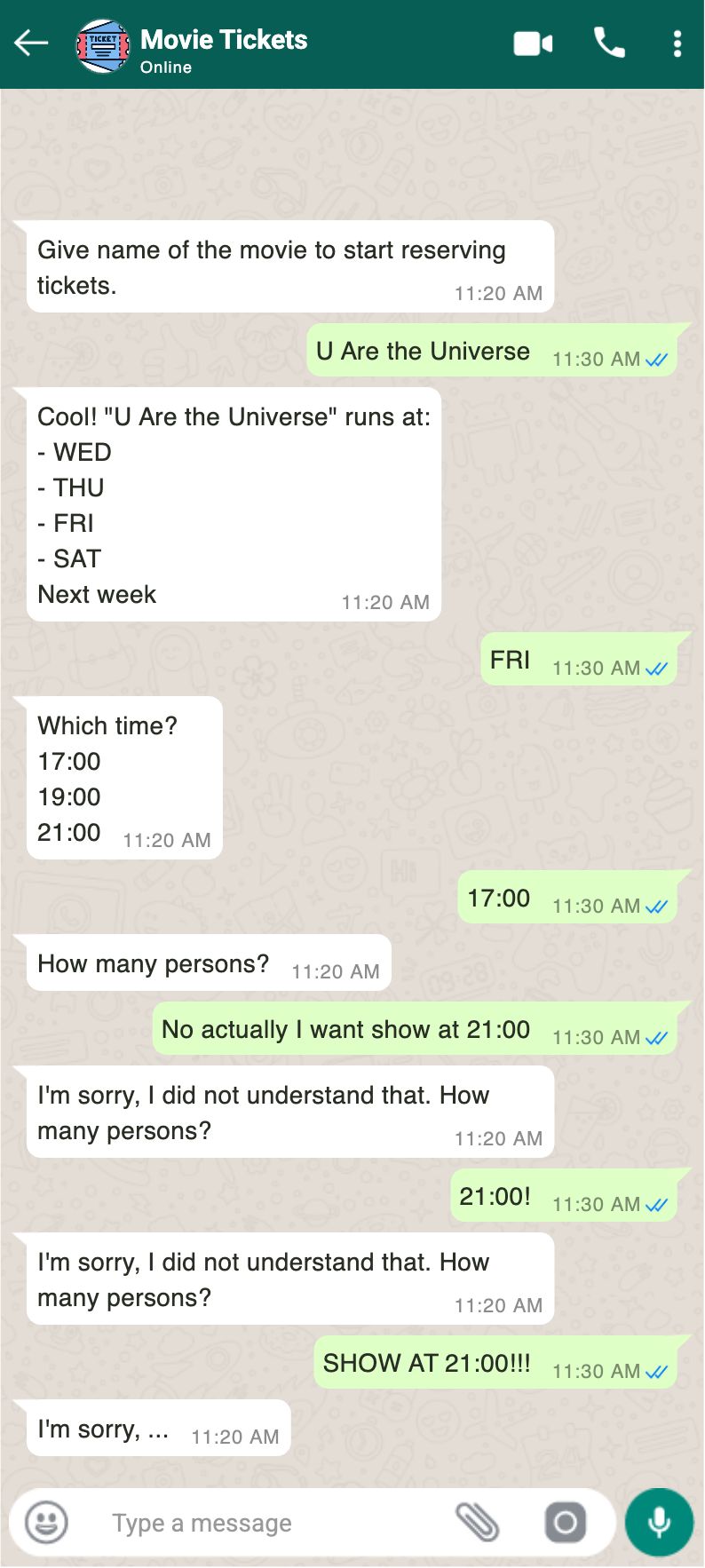

Large language models weren't available yet, so bot communication had to be structured through formatted, machine-readable messages. An interesting aspect of bot algorithms was (and still is) structuring and programming bot action logic. A big problem was that bots were typically "calcified" or "recalcitrant" because they operated based on rigid scripts. The adjacent image shows an example of what messaging with a stubborn bot was like. With a little pride, I recall the state machine and graph-based bot algorithm I developed, which could guide bot behavior past hard-coded scripts and flows when user messages didn't match the bot's expected formatted response.

This kind of logic programming is still necessary and relevant today. Language models alone aren't suited for controlling everything: they are non-deterministic, slow, expensive, and can behave unpredictably — making purely LLM-based control a security risk. Now we have wonderful models that understand natural language, but we also need something that moves the solution and user forward, from state to state. Sometimes the solution needs to call a tool or even end the interaction with the user. Such work is still being done, and LLM frameworks like LangChain and LlamaIndex aim to streamline the state transition logic of AI solutions. Manus AI (now owned by Meta) also built an impressive autonomous agent by cleverly combining language models and algorithms.

First Position as a Machine Learning Engineer

I got my first machine learning engineer position at UltimateAI (now "Zendesk AI Agents") at the end of 2018. I had been studying machine learning on Coursera courses (the meme below is surely familiar to those who studied on Coursera ML courses) for some time, and I have a good background in relevant mathematics and statistics. Now the time and available methods were also at a sufficient level for NLP purposes. Unlike previous jobs, this involved real machine learning methods and a data science approach.

One way to describe machine learning and data science is to say it's data-driven. Working with large datasets—understanding and processing them was familiar to me from my Leiki Oy days, but at Leiki the methods for processing and understanding datasets weren't very formal. I had to bring the statistical thinking to the work myself. In contrast, at UltimateAI we started from a machine learning native foundation, so datasets were explored and analyzed with statistically justified methods that had been refined over the years into largely the toolkit that data scientists use. We didn't try to reinvent the wheel but applied generally known and proven methods.

I had only gotten to use machine learning methods in courses before my time at UltimateAI. At UltimateAI, the core of the work was machine learning: tuning network training processes, adjusting inference, and AI infrastructure. The most effective way to learn something new is to get to do it with a good team. UltimateAI was an excellent place to learn machine learning and data science in practice. At UltimateAI, we trained models, utilizing and experimenting with everything freely available: FastText models and then transformer-based models, Universal Dependencies language resources, and UDPipe models. Every NLP solution had to be built from scratch: classification, entity extraction, sentiment analysis, etc.

During my time at UltimateAI, I also noticed a significant attitude change. I had been doing NLP for almost ten years and had had many conversations during that time. Before UltimateAI, when I told people about my work, the typical reaction was "meh", the listener's gaze would start wandering to the crown molding, and I've witnessed some pretty massive yawn bombs. In contrast, after starting work as a machine learning engineer, the general attitude changed. Old friends sent messages saying "what you do is the hottest thing" and sometimes I had to literally shake the curious ones off my ankles.

Hints of Things to Come

I'll start this section with the following meme, which (or something similar) I saw in UltimateAI's Slack sometime in 2019-2020.

Before anything great had come out of OpenAI's pipeline, OpenAI was spending enormous sums on training language models. At the time, it wasn't common knowledge that large language models would change the world so radically. Of course, compared to today, the AI investments back then were pocket change, but at that moment with uncertainty prevailing, they were absolutely mind-blowing.

Eventually, OpenAI broke through massively in 2022 after the release of ChatGPT.

A Few Final Notes

Customer-facing NLP work has changed dramatically since large language models arrived. It's no longer done with the same methods, tools or abstraction level. Neural network training and much of the wrestling with natural language details have been hidden under the hood at the language model vendor and framework level. Solution needs are satisfied with prompting and LLM frameworks.

In my opinion, the title "machine learning engineer" has experienced inflation. When it comes to customer-facing development work, few "machine learning engineers" work with or are even aware of machine learning details. AI engineer is a more fitting term in my view.

Methods have changed but the domain is the same: natural language processing using artificial intelligence. Currently, NLP engineers' work includes context management, prompting, solution orchestration, model selection, guardrailing, and evaluation. Here are some observations on how these work topics have changed entering the LLM era:

- previously prompting wasn't the main tool but rather a specialty that occasionally had to be relied on—for example, when enriching data or otherwise augmenting datasets

- orchestration is essentially the same in principle but now there are many different frameworks and ready-made services available

- we used to evaluate which AI model would be the best for each problem, but the majority of models weren't generative

- guardrailing existed but methods were different: for example, blacklisting, input and output validation, and filtering

- evaluation and metrics have become completely different because generative model outputs are not deterministic or in machine-readable format (Scorable (Root Signals) works on the specific problem of evaluating LLM performance)

- context management is perhaps quite similar to before: context poisoning and context dilution were a thing before the LLM era, but the difference is that security issues related to context manipulation only appeared in the LLM era, when AI started understanding and acting based on free text

Those are my thoughts for now. Thanks for your interest, and feel free to leave a comment on LinkedIn or get in touch!